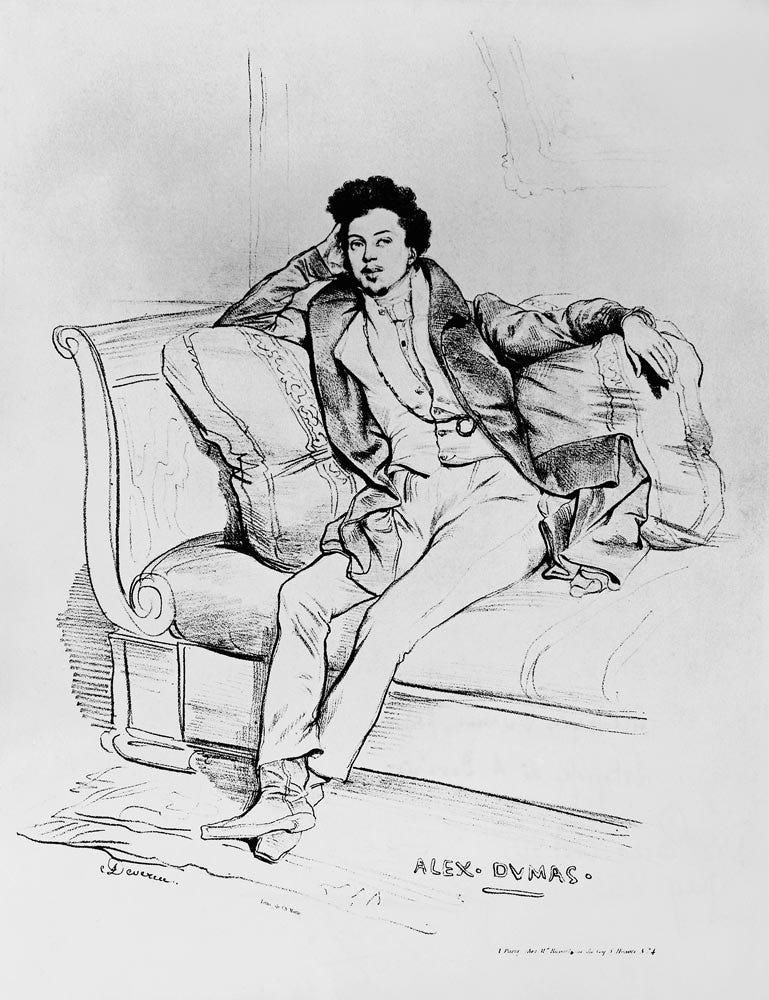

The 19th-century French author, Alexandre Dumas père (1802), was a true bon vivant and passionate cook. When he wasn’t writing, he could be found in the kitchen of his beloved Château de Monte-Cristo in Le Port-Marly preparing gastronomic delights for everyone who dropped by – and there was no shortage of visitors. Dumas, a generous and exuberant host with a chat as witty as his pen, liked to amuse his table companions with the most delightful stories. He traveled extensively and amassed a vast knowledge of food and cooking techniques throughout his life, which he captured in his final and often overlooked masterpiece, Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine.

Published two years posthumously, this epic culinary encyclopedia contains a staggering 1,200 pages of appetizing anecdotes and favorite recipes – some rather extravagant, such as his chapon aux truffes made with “a pound of bacon and two pounds of good truffles.”

Dumas was born in Villers-Cotterêts, not far from Paris. As a child, he showed great interest in literature and spent his time reading. At the age of 20, he moved to the capital and got a job as a copyist at the court of Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans. There, his love for theater blossomed and he began writing romantic comedies and dramas. After his first major success, Henri III et sa cour (1829), his plays became so popular that he was able to devote himself entirely to his writing career. He also wrote short stories, essays and travelogues and was an acclaimed novelist. Les Trois Mousquetaires and Le Comte de Monte-Cristo (both published in 1844) earned him great fame worldwide.

In 1846, Dumas bought a country house, Château de Monte-Cristo, named after his famous novel.

There, he lived like a king and delighted in a privileged existence with everything his heart desired. And that was mostly indulging his affinity for cooking. He wasn’t a big eater and drank little, but he liked to be around people and was proud of his culinary prowess. In 1861, the English journalist Albert Dresden Vandam saw how Dumas prepared a sumptuous dinner of carp, soupe aux choux, roasted pheasant, ragoût de mouton à la Hongroise and a Japanese salad. Vandam was so enamoured with Dumas’ cooking that he devoted an entire chapter of his book An Englishman in Paris to his incredible skills.

“He was assisted by his own cook and a kitchen maid, but he did everything himself, with his sleeves rolled up to the elbows, a large apron around his waist and a bare chest. I don't think I’ve ever seen anything so amusing,” Vandam wrote.

Courbet was also quite impressed by his talents. They often cooked together, singing and laughing, and sometimes Courbet would take his friend Monet along, who also admired the flamboyant Dumas and his delicious dishes.

Dumas liked to spend his money on the lavish dinner parties he all too often hosted for anywhere from ten to one hundred guests, but in his final years, unfortunately, little was left of his fortune and illustrious career.

In 1869, he retired to Roscoff to write his apotheosis, Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine – not a boring dictionary, but an informative and accessibly written piece of culinary prose that is a pleasure to read. Dumas wanted “to be read by people of the world and put into practise by people in the field.”

In the book, historical accounts and special encounters are interspersed with cooking tips, descriptions of more than 3,000 ingredients and recipes that give us a glimpse into the cuisine of the 19th century and the spirit of the writer. Some keywords leave our mouths watering, while others are not exactly appetizing to the modern reader or picky eater. Although the recipes are not very accurately written, with a little culinary know-how and some degree of imagination, you can make his charlotte russe, tomato omelette Provencal, petits pois à la ancienne, cherry soup, apricot flan and many other dishes.

Should you be curious about the preparation of elephant, you will find a recipe for the legs (one of the tastiest parts, according to Dumas) with garlic, chillies, Madeira wine and Bayonne ham. “The reader should not be deterred by this title,” Dumas reassures us, “because it is not my intention to let him eat this enormous animal entirely. But if he happens to have a trunk or a leg to hand, I would advise him to taste it (...).” The preparation of shark, kangaroo, swan, blackbird and bear from the Pyrénées is also discussed. Even the slaughter of a turtle is covered, and in a rather gruesome way:

“Tie the turtle to a ladder, hang a weight of 25 kilos from its neck, cut its head off with a sharp knife and leave it to bleed for five or six hours.”

Eagle, on the other hand, is spared of all cruelty:

“The grandeur, nobility and pride of the king of birds does not make its flesh any more tender or refined, for everyone knows it is tough, full of fibre and not tasty, and that the Jews were not allowed to eat it. So let it soar through the air and defy the sun, but do not eat it.”

Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine also contains many humorous anecdotes. Under ‘fig,’ Dumas tells us about the mischievous servant who had to bring two figs from the first harvest to Georges Louis Leclerc, Count de Buffon. On the way, he couldn’t resist temptation and ate one. “How could you have done this?” exclaimed Buffon. The servant took the remaining fig, put it in his mouth and, swallowing, said: “Like this!'”

A few months before his death on 5 December 1870, Dumas gave his manuscript to publisher Alphonse Lemerre. Unfortunately, the Franco-Prussian War was raging its evil and France was on the verge of starvation. Bad timing for publishing a book on food. Le Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine appeared in 1872, but received little attention. Dumas’ loyal readers were not interested in a ‘cookbook,’ and many critics found it messy and full of inaccuracies. Nevertheless, Dumas can rightfully be added to the list of great culinary writers of the 19th century such as Brillat-Savarin, Grimod de la Reynière and Antoine Beauvilliers. His latest work was a tribute to what had brought him the most joy in life: and that was not only food, but above all pleasure. He summed it up well under ‘dinner,’

“Everyday act of the utmost importance, which can be performed with dignity only by people of spirit, for during dinner one should not only eat, but it should also be taken with modesty and serene gaiety. The conversation should sparkle like the ruby red of the wines with the main course, it should be pleasant like the sweets for the dessert and intense like the coffee.”