Moments before my flight to Amsterdam is scheduled to depart, I receive a call from The New York Times requesting an interview about Rocamadour in the Lot department. I’m honored, but, at least for now, my thoughts are far from my beloved France, so I politely cut the call short and promise to get back to the reporter as soon as my plane lands. Physically, I’m still in Italy—Milan, to be precise—and my head is only beginning to process a short but intensely impressive trip to the Langhe region in Piedmont. In the past 48 hours, I’ve dined with wine producers from the Albeisa Consortium, attended a tasting session featuring Barolo, Barbaresco and Roero DOCG wines and learned about the characteristic Albeisa bottle, discovered the city of Alba from an archeological perspective, waved adieu to my fear of heights and braved a climb to the top of two towers (the Barbaresco Tower and the tower of the beautiful San Giuseppe Church in Alba) to revel in spectacular views, spent a morning hunting for black truffles and had my thoughts of starting a cooking school in France cemented after spending the morning in Fernanda Giamello’s convivial kitchen. My heart is French, but with each consecutive trip to Italy, I find myself more deeply enchanted by its culture, wines, cuisine and people, realizing I’m making room in my life for a blossoming love affair with this magnificent country.

A love affair begins

From Milan-Malpensa Airport, it’s a roughly two-hour trip southwest to Hotel Relais Montemarino, an ancient 19th-century farmhouse (once known as ‘Cascina Bagnolo’) tucked into the rolling hillsides of the Langhe and now offering a stunning setting for anyone visiting the region. In fact, you’re only a twenty-minute drive from Alba, the historical capital of the Langhe and the throbbing heart of this gastronomic paradise, known, among other delights, for its tartufo bianco. After a very early morning start, I arrive at this haven of tranquility and immediately leave the stresses of traveling behind me. The rooms of Montemarino still bear traces of its past in the form of gorgeous terracotta floors (which I have a notable weakness for) and vaulted brick ceilings. Outside, the far-reaching views of the countryside are green and lush. During my stay, I make a point to spend an hour at the bar’s terrace, with pen, paper, quiet contemplation and the soothing sounds of nature. My concentration is only interrupted once, by a couple walking back to their lounge chairs, hand in hand, after ordering an aperitivo. This is definitely a place to love and fall in love. And speaking of falling in love, later that afternoon, I would also be falling in love—with the regional wines, that is.

Dinner with Albeisa vintners

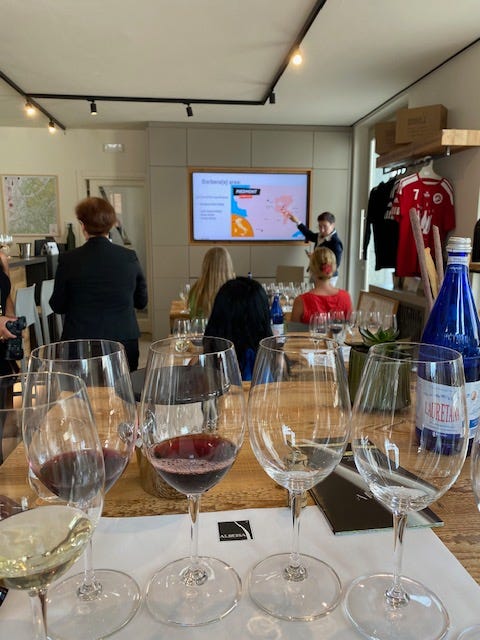

After a short introduction about the region and its wines at the headquarters and tasting room of the Albeisa Consortium in the heart of Alba by president Marina Marcarino (who also happens to be the forward-thinking woman behind the Punset winery in nearby Neive), I swoon as I swirl, sniff and sip.

The consortium is dedicated to promoting the exceptional wines of the Alba region, and central to its identity is the distinctive Albeisa bottle. In 1973, visionary Renato Ratti and 16 other producers revived this historic bottle, known as the B.O.C.G. (Bottiglia di Origine Controllata e Garantita), modernizing it with the name ‘Albeisa’ embossed four times around its shoulder for easy recognition.

The bottle’s origins trace back to the 18th century, when Piedmont winemakers and Antiche Vetrerie glassmakers in Poirino, near Turin, created a unique design reminiscent of both Burgundian and Bordeaux bottles but with distinct features. Today, the consortium oversees the use of this bottle, enforcing strict regulations to uphold its quality and uniqueness. Over time, the Albeisa bottle has adapted to contemporary needs. In 2007, a lighter version was introduced to promote sustainable viticulture. Utilizing the Albeisa bottle signifies a commitment to a longstanding tradition of bottling only the finest wines, providing immediate recognition of a wine’s origin and symbolizing the quality and heritage of the Langhe and Roero regions. In 2023, Albeisa comprised 316 members who produced around 24 million bottles. I dined with some of them that evening and was fortunate enough to taste their wines and discover more about what drives them and what makes the region so iconic.

Among them Maurizio Ponchione, a fourth-generation winemaker from the Roero who has 12 hectares planted with Barbera, Nebbiolo, Dolcetto, Grignolino, Chardonnay and Arneis; Luca Monchiero, a young, fourth-generation winemaker whose family’s viticultural roots are anchored in Castiglione Falletto, in the heart of the Barolo region (Luca, who has been working alongside his parents and brother since 2017, mentioned they also have some vineyards in Treiso in Barbaresco, where his mother is from); Veronica Santero, whose family has been making wine since 1974 in Serralunga d’Alba at Cantina Palladino (especially known for their classic Barolos) and Marina Marcarino, the aforementioned president of the consortium, who especially impressed me.

The regional wines flowed as we indulged in the kind of multi-course feasts that only Italians can do. One of the dishes I was served was an aromatic soup of chickpeas and farro wheat, delicate in consistency, yet at the same time rustic and bold in taste.

The meal was a perfect orchestration of regional fare that included beautifully cooked vegetables, pasta, sweets and more. In short, a delightful Italian banquet. Especially memorable, however, was the ambiance. Ostu Di Djun, a convivial (albeit a bit quirky!) osteria in the hilltop village of Castagnito, is an experience like no other I’ve ever had. It wasn’t only the pleasures of the table and the great company that were uplifting. Luciano (the owner, bursting with equal parts flair, passion and eccentricity) kept us well entertained with his exuberance, often throwing in a “pipireeeee” as he brought out the dishes.

During the dinner, each wine producer introduced themselves and said a little about the wine they had brought. When Marina (also a fourth-generation winemaker and the first in the family, who, at the age of 20, decided to bring the wines to market) mentioned she’s been working organically since 1982, I was immediately intrigued. “I proposed organic growing for our estate at a time when organic wasn’t fashionable,” she explained. In fact, they were the only ones working organically at the time. “From 1990, we also started working biodynamically and naturally. And as of 2007, we’ve been following the method of Japanese agronomist Masanobu Fukuoka. Our approach to the vineyard is a personal approach toward each plant. I think it’s very important to let the terroir speak; for the fermentation, we mainly use cement rather than steel or wood.”

We try her 2022 Barbera d’Alba, a pleasant, easy drinker with prominent aromas of red fruit, ripe cherries, a balanced acidity and refreshing finish. “I think it will go well with the tajarin (a thin variety of pasta from Piedmont) and the cheeses, but I’m not quite sure how it will pair with the chickpea soup,” she tells me. Honestly, however, I’m mainly interested in finding out about the way she works. So I lean over to find out more.

Forward-thinking

“We have 17 hectares of vineyards, and our average consumption of fuel for the tractors (work is mostly done by hand) is 600 liters a year, which is very little.” Rainwater is also harvested, and this year, it was plentiful. “With the exception of this vintage, which has been one of the worst in the last 20 years due to the heavy rains in spring, normally speaking, we use one-tenth of the amount of copper that we are allowed,” she tells me. Three kilos are permitted per hectare. Rather than using chemical sprays, copper sulfate is used by organic vintners to combat downy mildew. But used in high quantities, it can be detrimental to the soil microbiome.

“It’s not just about avoiding putting something in the atmosphere, but also about avoiding putting something in the soil,” she points out. “Copper remains in the soil and takes a long time to be absorbed.” Marina was captivated by Fukuoka’s natural farming philosophy. “I read his beautiful book, One Straw Revolution (1975), which explains the connection between the different relations and commitments within an environment. He used the woods, which is a perfectly balanced biosystem, as an example. We never think of planting something in the woods or changing things in any way. Would we cut the grass in the woods? Modern agriculture is killing the planet.”

Fukuoka’s natural farming agricultural philosophy emphasizes minimal human intervention and working in harmony with nature. His approach, also known as ‘do-nothing farming,’ advocates for the abandonment of modern agricultural practices such as tilling, chemical fertilization, weeding and pesticides. Instead, it promotes a deep understanding of natural ecosystems and their self-sustaining capabilities. By demonstrating that high yields can be achieved with low input, Fukuoka’s natural farming challenges conventional agricultural paradigms and encourages a return to more harmonious and sustainable production systems.

“When I started working like this, I was fascinated because I really think this is a way to give the planet a chance to breathe. But we are just a drop in the ocean.” As she spoke, it struck me that she isn’t just producing wine; her work and dedication are echoing with the rhythms of nature. By adopting Fukuoka’s methods, Marina is planting seeds of change, not just in her vineyards, but in the minds of those who are willing to rethink how we grow our food and care for our planet.

Of truffles and wine

The following morning, I awakened to a pristine blue sky, with thoughts about the previous day’s experience still whirling in my mind. While sipping my coffee and enjoying the already balmy temperatures, I glance over today’s programming, which is kicking off with a truffle hunt. I adore truffles (both Italian and French) and have written extensively about them (here, here, here and here, for example), but especially in recent times, they have been a source of controversy. In Italy, particularly in regions like Tuscany, Piedmont and Umbria, there has been a troubling rise in cases of truffle-hunting dogs being poisoned. This controversy stems from fierce competition among truffle hunters, as truffles are highly prized and valuable. Some hunters resort to malicious tactics, such as leaving poisoned bait, to sabotage rivals and protect lucrative truffle-rich areas. Authorities and truffle hunters with a real heart for their animals (as this NYT article reports) are increasingly concerned and working hard to combat this illegal activity.

As a real dog lover who is very in tune with canine behavior, I noticed how content and loved the two dogs that led our hunt were. Affectionate, cheerful and constantly showered with love and attention by their owner and those in our group, it was evident that they were living happy lives and being treated well.

And I’ve come to the same conclusion while investigating truffles in Dordogne. Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, of course, but personally, I believe that while the poisoning incidents are terribly unfortunate, I do not see truffle hunting with dogs as animal cruelty and will continue to enjoy truffles. And if you want to do the same, there’s no better time to do so than in the late autumn and winter, when Alba’s white truffles will seduce you with their exquisite aromas. Come October, food connoisseurs from all over the world will be flocking to Alba for the 94th edition of the white truffle festival, held this year from 12 October until 8 December.

After the truffle hunt, we hop in the car for a scenic tour of the region’s gently undulating vineyards while our guide tells us about the area. She mentions, for example, that Nebbiolo, the area’s most important grape variety (notably used to make Barolo and Barbaresco, both revered for their complexity and aging potential), likely takes its name from the Italian word for fog (‘nebbia’). “Originally, the grapes were harvested in November, when it was really foggy,” she tells us. She then goes on to talk about the subject vintners are struggling with, and one that we cannot (and must not) ignore: climate change.

“After 2017, winemakers realized that a change had definitely taken place,” she says. “Though this year has been quite different because of the excessive rain, the past years have been extremely hot. Winemakers are therefore trying to modify the work in the vineyards, especially the way they treat the leaves. Whereas in the past they used to cut the leaves during spring to let the grapes get more light, now, they are leaving the foliage as a sort of umbrella in order to protect the grapes. Additionally, vintners are working more and more sustainably. Many producers have introduced bees to help with pollination as well as green manure.”

Green manure refers to plants, often legumes like peas or beans, grown and then plowed into the soil to improve fertility and health. In vineyards, green manure enhances soil fertility by fixing nitrogen, improves soil structure and aeration and increases organic matter. It also helps control erosion, suppresses weeds and can aid in pest and disease management by attracting beneficial insects and producing natural suppressants. These benefits lead to healthier vines, better grape quality and more sustainable farming practices. Integrating green manure into vineyard management promotes a balanced ecosystem and long-term vineyard productivity. “Climate change is really here, and it’s not an exception,” she rightfully points out. “We know that we have to deal with it.”

We talk about the regional gems, such as Barolo, often referred to as the ‘King of Wines’ and produced in 11 villages. This prestigious Italian red is made exclusively from Nebbiolo grapes and renowned for its powerful structure, high tannins and complex flavor profile, featuring notes of cherries, roses, tar and truffles. It must be aged for at least three years before release, with many benefiting from extended aging. Its regal reputation stems from its historical association with Italian nobility and its esteemed status among wine enthusiasts, making it a benchmark for quality and excellence in winemaking.

“Our other grape varieties, such as Dolcetto and Barbera are really the wines that our grandparents drank,” she tells me. “My nonna and my nonno never drank Barolo, except on special occasions, so Dolcetto and Barbera were really the everyday wines. Of course, for aging Nebbiolo is the most important.”

As we head to Barbaresco, she tells us about the soils: “Thirty million years ago, these hills and the northern part of Italy were covered by sea. Basically, our soil is like a tiramisu of different layers. We have sand, marl, iron and above all, a lot of calcareous soil.”

While Barolo is known as king, the softer and approachable Barbaresco is queen. Aged for a minimum of two years (with nine months in oak), Barbaresco exhibits ethereal, fruity aromas in its youth and develops its complexity and spicy notes as it ages. How to pair it? In my opinion, with tagliatelle and porcini!

Our tour ends at La Torre di Barbaresco, which towers at a height of 30 meters and dates back to the end of the 11th century. I am terrified of heights, but I braved the climb in order to feast my eyes over the gorgeous vineyards.

The day carried on with a tour of Neive, a picturesque village known for its medieval architecture, narrow cobblestone streets and charming atmosphere. Neive, surrounded by rolling hills and scenic landscapes, offers a glimpse into traditional Italian life and is a haven for those seeking tranquility and natural beauty. Local restaurants and cafés offer delicious Piedmonte cuisine, making Neive a delightful destination for visitors looking to experience the region’s rich heritage and warm hospitality. Our lunch, which takes place at Bottega dei 4 Vini, starts with a glass of Pasquale Pelissero’s Alta Lange, a delicately sparkling wine with hints of stone fruit. It’s not only a perfect start to the meal, but also a much-needed refreshment after our truffle hunt and walks.

The culmination to day two took place at L’Argaj’s beautiful terrace, again, in the company of Albeisa producers, who did not fail to impress with their elegant offerings, which paired perfectly with yet another memorable Italian feast.

Before my departure the following day, we head back to Alba, where the amicable Fernanda Giamello of Effe FOOD is waiting in her beautiful kitchen to treat us to a cooking lesson, a final indulgence before waving the region arrivederci, at least for now. Besides the delectable peaches stuffed with dark chocolate, I was moved in another deeper, more personal way.

After teaching cooking in my home in the Netherlands ten years ago or so, a dream, which I still have to this day, blossomed: opening a cooking school in France. And this is exactly the vision I have had for so many years. From the style of teaching to the lovely dining room and beautiful vintage crockery. In life, there are no coincidences. This trip was one and all inspiration.

With thanks to AB Comunicazione & Consorzio Albeisa

Video of my experience, made by Hans Westbeek.

.