Wine lovers today have more choice than ever. Beautiful Cabernet Sauvignons come not only from France, but also from Chile, Australia and the United States. Even in the Netherlands we make beautiful wines in all colors and styles that are proudly served in our top restaurants. Take Restaurant Rijks, for example, which received the Wine Spectator Award in 2020 for an impressive menu with no fewer than 30 national stellar selections. Countries such as China and India are successfully making their way into viticulture as well, but that wasn’t the case 45 years ago. It wasn't until 1976 that a revolution started in the wine world – and that happened on May 24 in Paris during a blind tasting.

In 1787, Thomas Jefferson, Founding Father and Third President of the United States, made a wine tour through northern Italy and France. The wines from Gevrey-Chambertin, Meursault and Montrachet were particularly popular, and once back in Virginia, he had his favorite bottles imported. Remarkably, Jefferson was also optimistic about the viticultural future of his homeland. In a letter to French agronomist Charles Philibert de Lasteyrie, he wrote: “We could make as great a variety of wines in the United States as we do in Europe: not exactly the same variety, but no doubt just as good.” How great his joy (and surprise) would have been with the results of the tasting that went down in wine history as The Judgment of Paris.

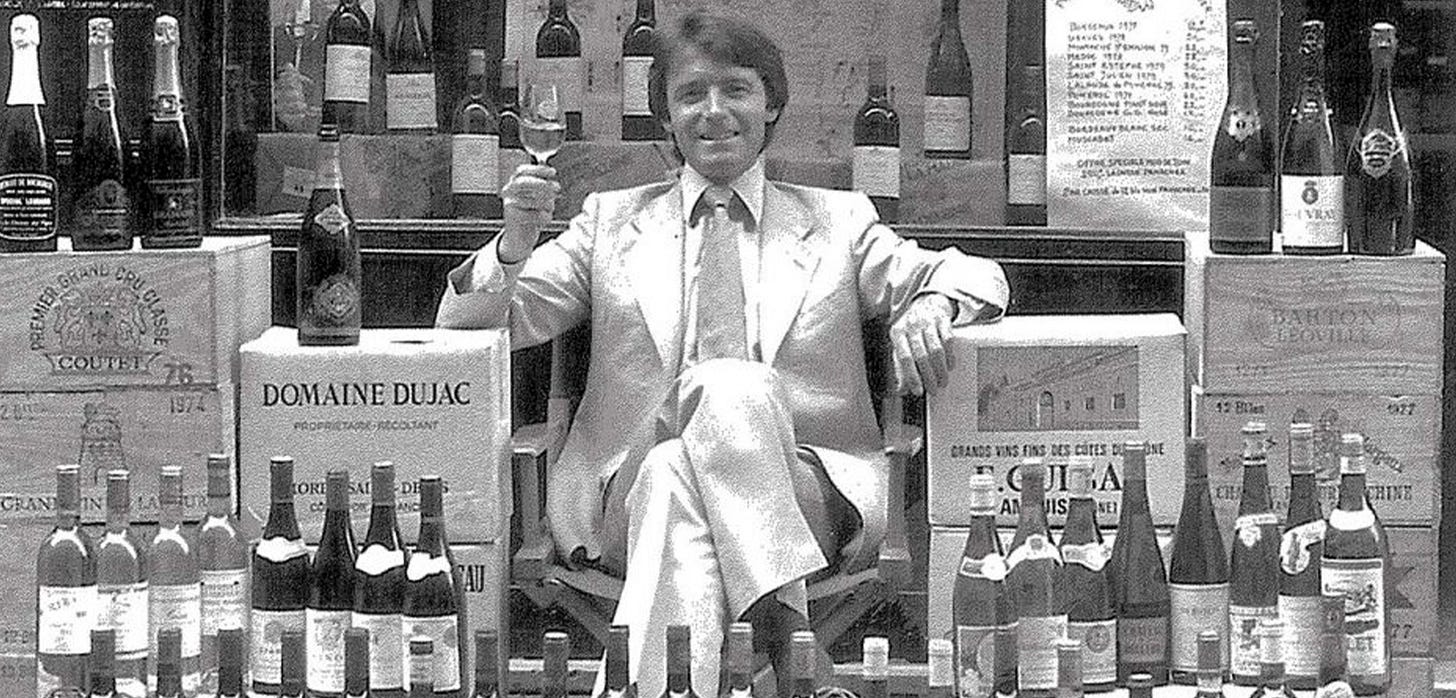

What was initially intended as a friendly dégustation on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the United States, swept aside the hegemony of French wine in a rather bewildering way. Steven Spurrier, a young and passionate English wine merchant, had the idea to introduce French wine experts to what California had to offer. In addition to his successful wine business in the middle of Paris, Cave de la Madeleine, he was also the founder of L'Académie du Vin, the first private wine school in France. Both ventures attracted many English-speaking customers, including California winegrowers and journalists who brought bottles for tasting. Apparently, something was going on in the Golden State.

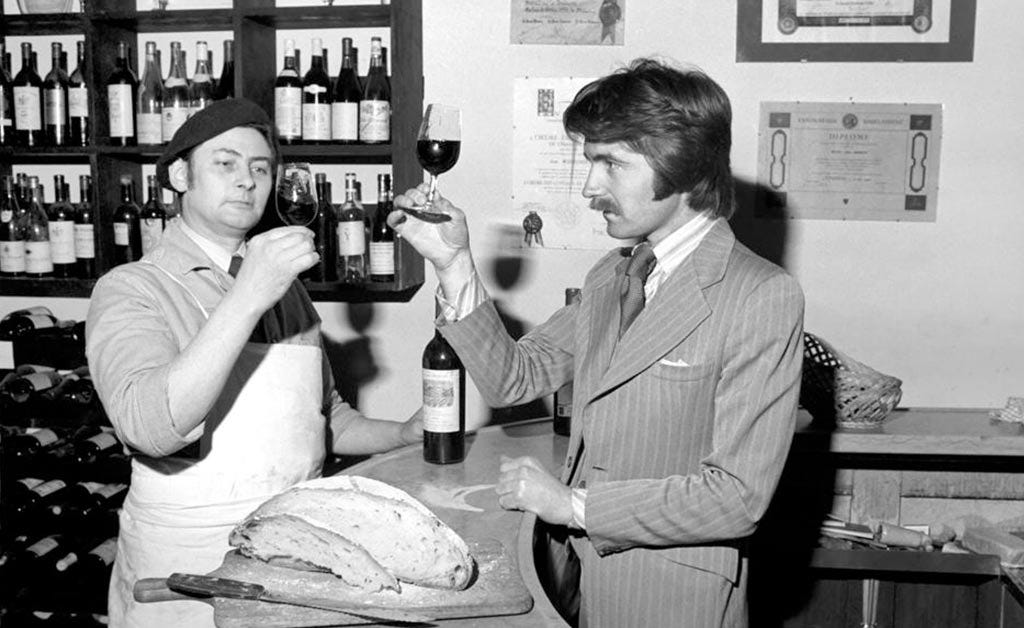

Spurrier not only had an eye for the most reputable houses, but could also become wildly enthusiastic about unknown producers in small regions. When hisAmerican associate Patricia Gallagher went on a trip to Napa Valley and returned very impressed with the quality she found there, Spurrier set off for California himself to select the wines for the tasting. On behalf of the Academy, they invited a distinguished nine-member jury to the InterContinental Hotel to sample six California Chardonnays and six Cabernet Sauvignons—all from small, up-and-coming wine estates. To avoid prejudice and increase the chances of recognition for the wines, Spurrier decided at the last minute to host a blind tasting with four white Bourgognes and an equal number of red Bordeauxs from his shop, all top-notch. When asked if everyone agreed with the proposal, the answer was: "Pas de problème."

As luck would have it, George Taber, who was working for Time Magazine back then, had room in his busy schedule and was also able to attend the event. Taber spoke and understood French well and soon noticed there was confusion among the judges regarding the origin of the wines. When Claude Dubois-Millot of Gault & Millau received the famous Bâtard-Montrachet, he was convinced that he was tasting a wine from California because it had “no nose.” In the first round of Chardonnays, each judge gave the most points to the California wines. Chateau Montelena from 1973 came in first place, above the Meursault-Charmes from the same year. In fact, three of the top five wines came from California.

Stunned and determined not to let this happen again, the judges went to taste the red wines with even more attention. What happened next? Although the French came out slightly better, first place went to the 1973 Stag's Leap Wine Cellars from Napa Valley, which outperformed the premier cru classés Mouton-Rothschild and Haut-Brion.

After Taber's article was published two weeks later in Time Magazine, California wine became booming business, but the reaction and criticism that followed from the French side was harsh. Jury members were seen as traitors or severely reprimanded. Odette Khan, editor-in-chief of La Revue du Vin de France, insisted there was cheating. Moreover, the French wines were still too young to be able to judge them fairly, and the wines from California would not be able to mature as well, others thought. That last argument was debunked 30 years later during two tastings that took place simultaneously in Napa Valley and London. The same ten red wines were again uncorked. Lack of bottle aging was definitely not the issue in 1976: the top five came from California.

What Spurrier's historic tasting ultimately proved is that excellent wines could be made anywhere in the world. Since then, New World countries such as South Africa, Chile and Australia have continued to develop with the realization that not only France is blessed with good terroir and passionate winemakers. The tasting from 1976 served as an example for unknown quality wines, which from that moment on, began to compete with the big boys. For example, in 2004, Spurrier hosted The Berlin Tasting, which also made history when Eduardo Chadwick's Chilean wines were chosen over French classics like Château Lafite and Château Margaux and the so-called Super Tuscans, including Sassicaia. In fact, The Judgment of Paris also gave new impetus to French winemakers whose prestigious viticultural histories had them proudly “resting on their laurels,” as Spurrier often said. Even Aubert de Villaine of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, one of the judges in 1976, admitted: “I was bored. Then I realized the beneficial effect. We didn't know we had competitors. This tasting gave us a kick in the behind.”

In 2016, 40 years after The Judgment of Paris, Steven Spurrier was honored by the United States Congress for his significant role in the wine industry. He was given a folded American flag that had flown festively in his honor over the Capitol for two days. Shortly before that, he had been invited to a special celebration at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History where the two winning bottles from 1976 were on display. “Having a bottle of Chateau Montelena and Steven Spurrier's name in the Smithsonian's permanent collection is an honor not to be underestimated,” said Bo Barrett, general manager and winemaker of Chateau Montelena.

And yet the wine revolution that The Judgment of Paris brought about is just one of Steven Spurrier's numerous achievements. Spurrier fell in love with wine at the age of thirteen when his grandfather let him taste a glass of Cockburn's 1908 on Christmas Eve 1954. His career began in 1964 in the cellars of Christopher's, London's oldest wine merchant. That same year, he was given a check for the equivalent of £5 million, a significant amount that he happily spent on art (actually his greatest passion) and various ventures in the wine world. After his marriage to Bella in 1968, the young couple left for France to start a new life, first in Provence and from 1970 in Paris. Steven opened his wine business in 1971 and the adjacent wine school two years later, where Michel Bettane (France's foremost wine critic) began his career as a teacher.

In the 1980s, he opened a number of restaurants in Paris (not all equally successful), wrote wine books and co-created the renowned Christie's Wine Course in London with his mentor Michael Broadbent. He returned to London in 1990 and in the following years opened branches of L'Académie du Vin in Japan, Italy and Canada. From 1993 to 2020, Spurrier was columnist for the British wine magazine Decanter, and in 2004 he launched the Decanter World Wine Awards together with then editor-in-chief Sarah Kemp. In 2017, he was named 'Man of the Year' by the magazine.

Spurrier was considered a “true gentleman” by everyone – the complete opposite of how he was portrayed in the film Bottle Shock (2008), by the way. Far from being a wine snob, he was always open and friendly. With inexhaustible enthusiasm he was always looking for the next challenge. He was in his 70s when he founded Bride Valley Vineyards in the chalky hills around his Dorset home and became a vigneron in English sparkling wine.

Because, according to Spurrier, there was a lack of solid wine literature, he started his own publishing house in 2019, the Académie du Vin Library, with both classics and new, inspiring titles. In late 2020, the publishing house partnered with the respected Napa Valley Wine Academy. In a series of free webinars, authors have their say and wine is sometimes tasted. Host Peter Marks (MW), who met Spurrier when he helped organize the 30th anniversary of the Judgment of Paris in 2006, last spoke to him in December 2020 and told me: “It was an honor to work with Steven. He was humble, always positive and loved life. Steven was fascinated by all the new wine regions and the many possibilities that wine brought him.”

In his book, A Life in Wine (2020), Spurrier wrote: “The secret to a happy life actually lies in three Ss – Someone to love, Something to do and Something to look forward to.” He died on 9 March 2021 at his home in Dorset.