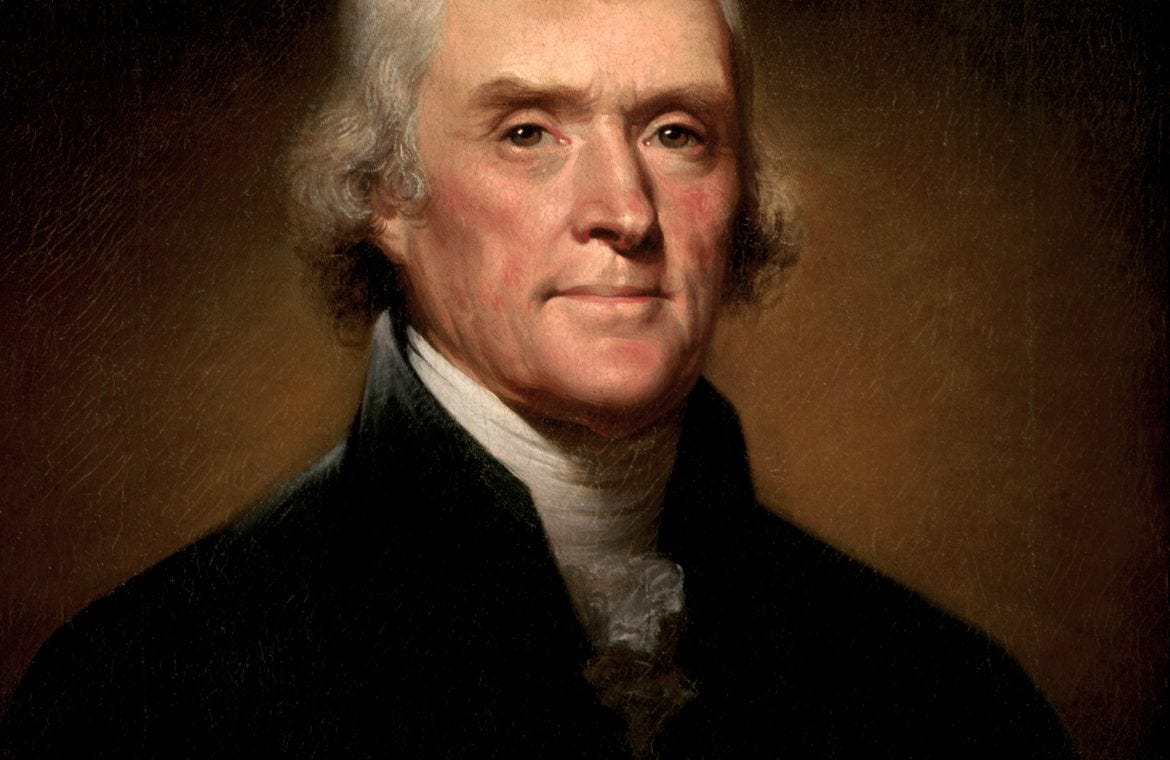

THOMAS JEFFERSON: FOUNDING FATHER & FRANCOPHILE

Long before Julia Child shared French cuisine with America, Founding Father Thomas Jefferson was tasting his way through France, discovering the country’s food, wine and culture.

Thomas Jefferson earned his place in history books as one of America’s Founding Fathers. Born in Virginia on his family’s wealthy plantation in 1743, he was the author of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States (1800-1809). What some may not know, however, is that Jefferson was a passionate food and wine connoisseur — and a true Francophile.

DEPARTURE FOR FRANCE

After resigning his seat in the Second Continental Congress in 1776, Thomas Jefferson was invited to France on several occasions, yet refused, apprehensive about leaving his family or subjecting them to a potentially dangerous journey overseas. In 1784, two years after the death of his beloved wife Martha, however, he agreed to join John Adams and Benjamin Franklin in Paris as US Minister Plenipotentiary to France. His world had fallen apart after Martha’s death, and Jefferson was ready to accept a new challenge and give meaning to his life once again. He arrived in Paris in 1784 in the company of his 11-year-old daughter Martha (Patsy) and his slave, James Hemings. With the departure of both Adams and Franklin, Jefferson was left as the sole representative of the US in France.

CAPTIVATED BY PARIS

It was during his time in France, one of the most memorable periods of his life, that Jefferson blossomed into a citizen of the world. Living in Paris meant being exposed to all the cultural treasures the French capital had to offer. He appreciated art and regularly attended exhibitions and auctions, he loved to read and was said to have purchased a book every single day, he attended the theater and was smitten by the plays of greats such as Molière and Dancourt, and he had a keen taste for architecture and music. In short, Jefferson was truly captivated by the elegance and culture of Paris.

A year after his arrival, he moved into a magnificent townhouse on the Champs-Élysées, the Hôtel de Langeac, which was designed by renowned architect Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin (also responsible for the Arc de Triomphe). There, he derived great pleasure in beautifying the rooms with artworks purchased at auctions as well as handsome furniture, silver and other fine objects.

FOOD & WINE CONNOISSEUR

But what especially sparked Jefferson’s interest while in France was the country’s food and wine. On February 28th 1787, he left Paris and embarked on a what could be called a most delectable wine journey through France and northern Italy. He toured through the vineyards of Bourgogne, Bordeaux and the Loire Valley, tasting as he went and becoming more and more enamored with the wines he discovered. In Beaune, he met Étienne Parent, wine merchant, master cooper and barrelmaker. Parent was not only his guide, taking him through the celebrated vineyards and great cellars of Pommard, Meursault and Volnay, but he also became his personal wine salesman. Jefferson was quite partial to the wines from Chambertin, Meursault and Montrachet, which often made their way to his dinner table. He also drank champagne and loved wines from Bordeaux. Notably, he took quite a liking to Sauternes from Château d’Yquem, calling it “the best white wine of France,” and treating himself to 250 bottles of the 1784 vintage.

Without a doubt, we can say that Jefferson was the first American wine connoisseur. When he returned to Virginia after his time in France, he had high hopes that his own country would one day, too, be able to produce wonderful wines such as the ones he tasted abroad. Imagine his delight if he would have had the chance to experience the vineyards and wines of California’s Napa and Sonoma Valleys!

Jefferson loved French cuisine and even arranged for his slave James Hemings to take lessons in the French kitchen while in Paris. During his tour of France, Jefferson took note of interesting crops and farming techniques, later introducing a wide variety of fruits, nuts and vegetables to the abundant gardens of Monticello, his exquisite mansion in Virginia. In Monticello, he employed French chefs and hosted lavish dinner parties, serving novelty cuisine such as vanilla ice cream and fried potatoes (French fries!). Intent on ensuring his daughter Martha would not forget what she had learned in Paris, he gifted her a copy of La Cuisinière Bourgeoise (one of the best cookbooks of the time) for Christmas 1791.

While in France, Jefferson blossomed into a real Francophile, declaring his love for the country in many of his letters and memoirs.

JOIE DE VIVRE

In 1786, for example, Thomas Jefferson hinted at the French ‘joie de vivre’ in a letter to Abigail Adams:

“Here we have singing, dancing, laugh, and merriment (…). When our king goes out, they fall down and kiss the earth where he has trodden; and then they go on kissing one another. They have as much happiness in one year as an Englishman in ten.”

GOOD TASTE & TEMPERANCE

Jefferson decorated Monticello in French style with many items from his time in Paris, everything from furniture to beautiful wine glasses, fabrics and kitchen utensils. In his dining room, he would often gather friends for food, wine and good conversation, just as he did while living in France. To him, there was an art to true enjoyment… and no one understood that art as well as the French. In 1785, he wrote the following to Charles Bellini:

“In the pleasures of the table they are far before us, because with good taste they unite temperance. They do not terminate the most social meals by transforming themselves into brutes. I have never yet seen a man drunk in France, even among the lowest of the people. Were I to proceed to tell you how much I enjoy their architecture, sculpture, painting, music, I should want words. It is in these arts they shine.”

WORDS OF A FRANCOPHILE

When Jefferson left France in 1789, he did so with great gratitude for the country and its people. In his autobiography, published in 1821, he penned his heartfelt love for France with the following words:

“And here I cannot leave this great and good country without expressing my sense of its preeminence of character among the nations of the earth. A more benevolent people I have never known, nor greater warmth and devotedness in their select friendships. Their kindness and accommodation to strangers is unparalleled, and the hospitality of Paris is beyond anything I had conceived to be practicable in a large city. Their eminence, too, in science, the communicative dispositions of their scientific men, the politeness of the general manners, the ease and vivacity of their conversation give a charm to their society to be found nowhere else. In a comparison of this with other countries, we have the proof of primacy which was given to Themistocles after the battle of Salamis. Every general voted to himself the first reward of valor, and the second to Themistocles. So ask the traveled inhabitant of any nation, In what country on earth would you rather live? — Certainly, in my own where are all my friends, my relations, and the earliest and sweetest affections and recollections of my life. Which would be your second choice? France.”